Today we have another obscure holiday for you. It's International Jazz Day, which is organised and recognised by UNESCO. UNESCO considers the objectives of this holiday to celebrate the "virtues of jazz as an educational tool, and a force for peace, unity, dialogue and enhanced cooperation among people". While this seems like a good reason to celebrate jazz, as per usual, we are more interested in the linguistic elements of jazz. First though, we need to really understand what jazz is.

You should already know that jazz is a type of music, shamefully dismissed by some as a way to be a pretentious hipster. In fact, jazz couldn't be farther from the pursuit of twenty-something white guys who sport vintage knitwear and enjoy only the obscurest of coffee-based beverages.

Jazz music started in the southern United States during the dawn of the 20th century as a lovechild between African and European music. When the harmonies of European music got together with African syncopation, swung notes, and improvisation, jazz was born.

|

| New Orleans, one of the best places to enjoy jazz music. |

Jazz as a noun in the English language used in reference to music is thought to have come from the Creole patois word jass which either means "strenuous activity" or refers to the act of love-making, which while strenuous, is also incredibly enjoyable, just like jazz music.

While the name for jazz shares its etymological roots with the ethnic roots of the music, the word for one of the most important aspects of jazz, improvisation, is wholeheartedly European in origin. Improvisation, like many musical terms, comes from Italian improvviso, then improvvisare, making its way into French as improviser, before finally arriving in the English language as improvisation. However, it wasn't until 1786 when this word had a musical connotation in the English language. From the fifteenth century, the word actually referred to the unpredictable or an "unforeseen happening", which pretty much perfectly describes improvisation.

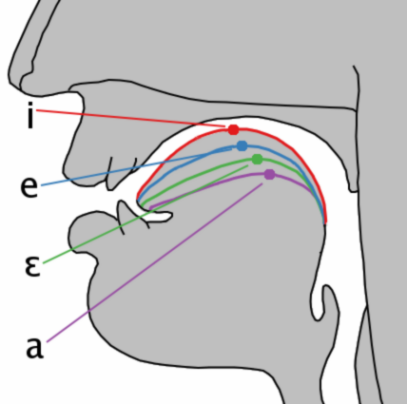

As you can see, these two words have both African and European origins, like jazz. In fact, the relation between jazz and language runs much deeper than mere etymology. Unfortunately, jazz music came about due to the deplorable slave trade in the United States in the nineteenth century. We think the slave trade was absolutely horrific, but the resulting jazz music is one of the very few good things to come from it. The obscure rhythms of jazz are inspired by the speech patterns of the African languages, so while music has shaped a lexicon, a family of languages could be said to have shaped jazz music entirely.

.png)